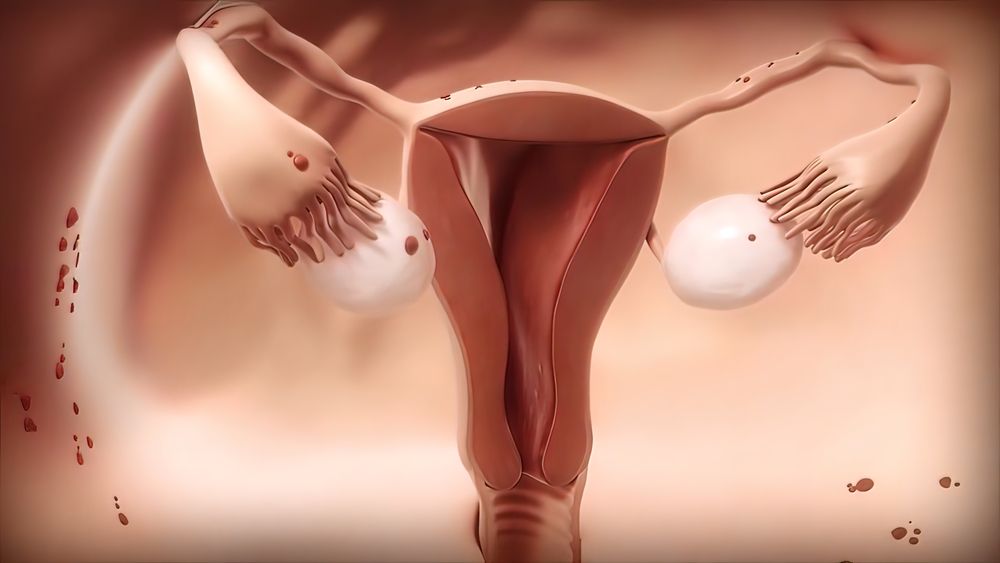

About 50,000 women are diagnosed with endometrial cancer each year. It is the most common gynecologic cancer and occurs when cells in the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) start growing out of control and spread to other parts of the body. Cancer of the endometrium is different from cancer of the connective tissue and muscle in the uterus, which is called a uterine sarcoma.

Endometrial adenocarcinoma is the most common type of endometrial cancer, making up about 80 percent of all endometrial cancer cases. It starts in glandular cells that develop the uterine lining, and it can spread to other tissues and organs in the pelvis or abdomen.

Some types of endometrial cancer are more aggressive than others, and they are harder to treat. Endometrial carcinomas are classified according to their appearance and how far they have spread when they are diagnosed. Type 1 endometrial carcinomas, also known as low-grade endometrioid carcinoma or EEC, are confined to the uterus and have a good prognosis. Type 2 endometrial carcinomas, including serous and clear cell carcinoma, are less common but have more aggressive features and lower survival rates than type 1 endometrial cancers. Type 3 endometrial cancers include ovarian papillary serous carcinoma, ovarian serous/transitional cell carcinoma and adenosarcoma of the uterus, which are all more likely to spread to other parts of the body than types 1 and 2.

Uterine stromal sarcoma makes up less than 5 percent of endometrial cancers and is more difficult to treat than other types. These cancers have a higher risk in women with a history of abnormal vaginal bleeding and may be difficult to diagnose because they tend to look like adnexal cysts or endometriosis.

The risk of endometrial cancer increases with age, but it’s rare for younger women to have this disease. Women who have had hysterectomy are less likely to get it, as are women who haven’t used birth control pills or estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy after menopause. The risk is also higher in African-American women than in white women.

Signs and symptoms of endometrial cancer can include unusual vaginal bleeding and pain, a pelvic mass or tenderness and an abnormal Pap test. A biopsy is needed to confirm a diagnosis of endometrial cancer. This procedure involves inserting a small needle into the uterus to remove a sample of tissue. A pathologist then looks at the sample to check for cancer. Another procedure, called dilation and curettage (D&C), is more invasive than a biopsy. It involves a more serious surgery to open the uterus, and it’s done when a biopsy can’t be safely removed.

Getting regular pelvic exams, Pap smears and vaginal ultrasounds can help prevent cancer. If you’re at risk for endometrial cancer, your health care provider can order these tests.

After treatment, your doctor will watch for signs that the cancer has returned. If it comes back, your doctor can give you more treatment. You may want to consider joining a clinical trial for new types of treatment.