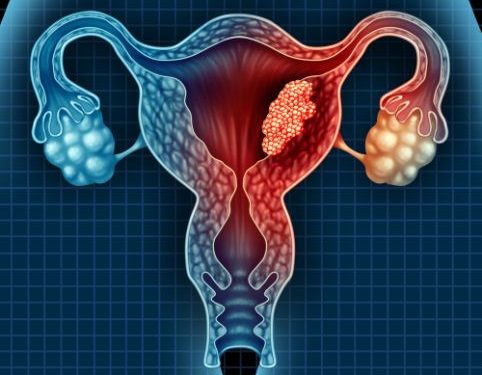

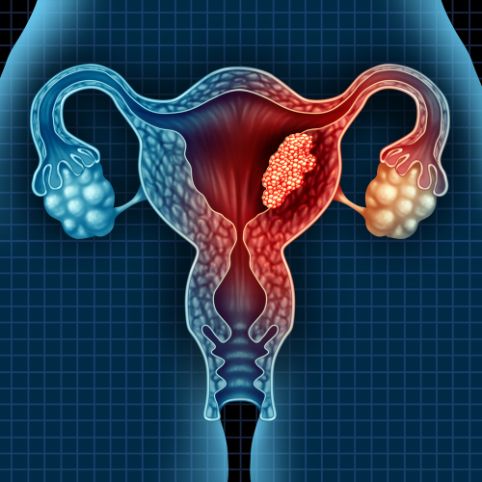

The lining of the uterus (endometrium) changes thickness throughout a woman’s life, growing and shedding in response to two hormones. During the reproductive years, estrogen and progesterone thicken the endometrium in preparation for implantation. If pregnancy does not occur, the lining is shed through menstruation. The process may become abnormal if a woman produces too much of one or the other hormone, which is what happens in people with endometrial hyperplasia. This condition can lead to abnormal uterine growth and tissue proliferation that can eventually cause cancer.

In women with abnormal uterine bleeding, it is important to evaluate the endometrium. However, it is not always possible to distinguish the underlying pathology by the presence of hyperplasia or carcinoma on ultrasound images alone. Despite the availability of less-invasive techniques, such as Saline Infusion Sonohysterography and hysterosalpingography, transvaginal ultrasound is often the initial test used to assess endometrial thickness.

Currently, the threshold for an endometrial thickness that should prompt a biopsy in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding is not well defined.1 However, a high-resolution gynecologic ultrasound with a curved obstetric transducer allows for the accurate measurement of the double layer of endometrium.

In a recent study, researchers found that in postmenopausal women without abnormal uterine bleeding, a pre-SHG double-layer endometrial thickness of 4 mm was associated with a low false-positive rate and no change in sensitivity compared to a lower cut-off of 3 mm.2

This research supports the need for a more-precise definition of an endometrial thickness that would be predictive of malignancy in postmenopausal women. It also emphasizes the need to include a variety of ultrasound features in evaluation of a woman with abnormal uterine bleeding, including focal thickening, a symmetric double-layer appearance, and disruption of a subendometrial halo.

As the population ages, more and more women are experiencing abnormal uterine bleeding. This can be a result of the natural aging process, or it could be due to certain health conditions and medications such as menopause-related hormones. In both cases, it is critical to evaluate the endometrium with a high-resolution pelvic ultrasound to ensure that the endometrial lining is not abnormal. The results of this research can help physicians establish a more-precise definition for an abnormal endometrial thickness, so that these patients can receive the right care. In the future, this will hopefully result in fewer unnecessary biopsies and reduce the need for invasive interventions like dilation and curettage.