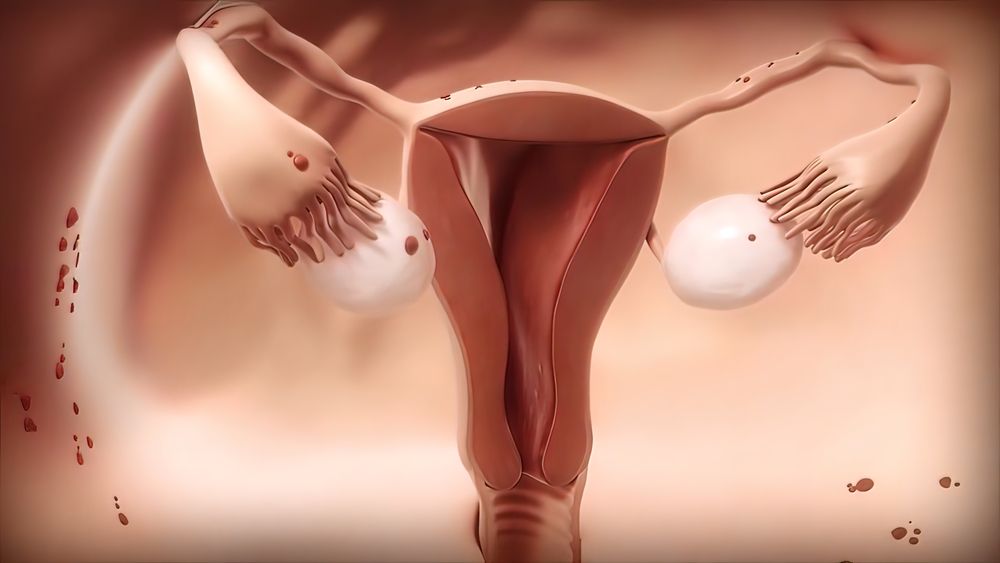

Endometrial is a thick tissue that lines the inside of the uterus. In healthy people, this tissue thins and breaks down during each menstrual cycle to prepare for the implantation of an embryo during pregnancy. But with endometriosis, this tissue grows outside the uterus — on the ovaries, on the pelvic walls or in the abdominal cavity. Over time, this tissue can create cysts and scar tissue that irritate surrounding tissues and organs. This may cause long-term (chronic) pain — especially during menstrual periods. It also can make it difficult to get pregnant, although treatment can help.

The causes of endometriosis aren’t known. But it’s likely that hormones or immune factors cause cells from the lining of the abdomen to change into endometrial-like tissue and implant on other areas of the body, resulting in endometriosis. There are several theories about how this happens:

In one theory, retrograde menstruation is the cause. During a normal period, menstrual blood travels down the Fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity. But sometimes this blood passes through the Fallopian tube opening and back into the ovary. This blood may then re-enter the body and start growing on other tissues in the pelvis. This process is called metaplasia.

Another theory is that endometrial-like tissue develops when peritoneal cells transform into embryonic cell implants during puberty. It’s also possible that the cells migrate from the ovaries and enter other parts of the body through the blood vessels or the lymphatic system. And finally, it’s also possible that endometrial cells migrate from a surgical incision after a C-section or hysterectomy to other areas of the body.

Women with endometriosis have a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer later in life, although there is no clear explanation for this. The ovaries have a high concentration of estrogen, which can encourage the growth of endometrial-like tissue.

As people age and go through menopause, the levels of estrogen in their bodies decrease. This decrease may be why symptoms of endometriosis improve with age and during menopause.

The first step in diagnosing endometriosis is a physical exam, including a pelvic exam and abdominal ultrasound. Your doctor may also order an MRI. The tests can help doctors find and measure the thickness of the endometrium. They can also show any cysts or scar tissue. A biopsy may be needed to confirm a diagnosis of endometriosis. The most common biopsy involves removing a small sample of the endometrial tissue. This can be done with a laparoscopy or vaginal speculum. This tissue can then be tested to determine if it’s endometrial or non-endometrial tissue. It can also be used to help determine the best way to treat the condition. Some people may benefit from taking oral or topical hormones, while others may need surgery to remove the endometriosis. This can be a lengthy process and requires patience, but it’s important to discuss all options with your healthcare team. The good news is that most patients with endometriosis experience improvement or resolution of their symptoms after treatment.