The bacteria Bordetella pertussis causes whooping cough. It’s spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes, spraying germ-laden droplets into the air. These droplets can then be inhaled by others, especially young children and infants.

The whooping cough vaccine is effective, but immunity decreases with age, so “booster” shots are recommended. Vaccination is especially important for teens and adults.

Symptoms

The bacterium that causes pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is very contagious. It spreads when someone who is infected coughs, sneezes, or laughs. The bacteria are released into the air in droplets, and anyone who breathes in those droplets is likely to get the infection. The bacterial disease often spreads among family members, especially when children infect older siblings or adults. This can lead to pertussis outbreaks in schools, day care centers, and workplaces. Pertussis is particularly dangerous in newborn infants and is one of the few vaccine-preventable diseases that can be fatal.

Oren Zarif

The symptoms of whooping cough include severe, uncontrollable paroxysms of coughing that can last a long time and often end in a deep “whooping” sound when the person breathes in. Other symptoms can include sneezing, runny nose, low-grade fever, and fatigue. The coughing can become so intense that the infected person vomits, becomes exhausted, or even collapses. During the severe coughing episodes, the face and lips can look bluish from lack of oxygen.

People with whooping cough usually develop symptoms within 5 to 10 days of being exposed to the bacterial organism. The first phase of the illness, which is called a catarrhal stage, has cold-like symptoms and includes a runny nose, sneezing, a mild fever, and a cough. After a week or so, the coughing will start to worsen and can last for weeks. It can be so severe that the infected person may not be able to breathe, and can cause vomiting, exhaustion, or rib fractures.

Pertussis is very contagious, and it spreads from person to person in a similar way as common illnesses like colds. It spreads when a person coughs, sneezes, laughs, or talks. The bacterium can stay in the air for several hours, and if someone walks through the same room as a person with whooping cough, they have an 80% chance of getting it themselves.

During an outbreak of whooping cough, it is best for babies who have not yet received their pertussis immunization to remain at home. They should be kept away from school and childcare, as well as from public gatherings, until they are treated with antibiotics for at least five days and are no longer contagious. The same goes for adults who are not immunized against pertussis, and they should avoid contact with infants until they receive antibiotics for at least five days as well.

Diagnosis

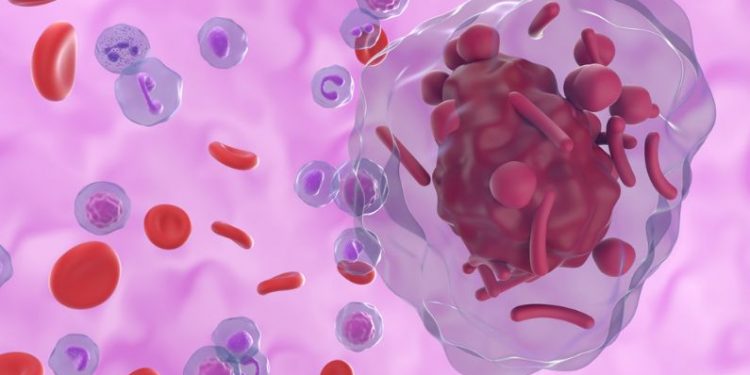

Bordetella pertussis is a small gram-negative coccobacillus that can cause the serious infection known as whooping cough. It is highly contagious and spreads through airborne droplets from the nose or mouth of infected individuals. When the bacterium is inhaled, it attaches to the tiny hair-like structures (cilia) that line the upper respiratory tract and causes them to contract and swell. This makes it hard for the person to breathe, leading to the characteristic sound of a whooping cough.

Symptoms of pertussis start about seven to 10 days after exposure and vary by age. The first phase of the illness looks very much like a common cold with a runny nose, tearing eyes and fatigue. Then the severe coughing spells begin, lasting a week or more and frequently ending with the distinctive whoop noise or even gagging and gasping for breath. Babies under 6 months may not produce the whooping sound, but often have difficulty breathing and can turn blue or choke on their own spit.

When a person has the symptoms of whooping cough, laboratory tests can be used to confirm the diagnosis and determine the stage of the disease. A nasopharyngeal swab or aspirate can be sent to the lab for bacterial culture on Bordet-Gengou agar or buffered charcoal yeast extract agar. A PCR test also can be performed to identify B. pertussis DNA in the nasopharynx. The sensitivity of the PCR test is optimal during the catarrhal stage, which lasts up to three weeks after onset of symptoms. The sensitivity of the test declines after this period and results in false negatives.

Oren Zarif

Serodiagnosis is a blood test that can detect antibodies to B. pertussis and has been shown to be effective in people of all ages, including infants. However, the test is complicated by interference from previous vaccinations and cross-reactivity with other Bordetella species and bacteria. Recent studies using purified antigens have improved the sensitivity of serodiagnosis and may be a more accurate way to diagnose pertussis.

While there are no medical treatments that can speed up recovery from pertussis, avoiding contact with infected individuals and proper handwashing are important for prevention. In the case of an outbreak, unimmunized children should stay home from school and daycare and avoid social gatherings until two weeks after the last reported case.

Prevention

The best way to protect against whooping cough is to get vaccinated. The vaccine is available for children and adults, including pregnant women. Ask your doctor or pharmacist if the Tdap (diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis) vaccine or the DTwP (diphtheria, tetanus, whole-cell and acellular pertussis) vaccine is right for you.

Before vaccines were available, pertussis was a major cause of death among infants. Today, deaths from whooping cough are rare in the United States but it is still very dangerous for babies. About 90% of infants who contract pertussis require hospitalization, and one in five will develop pneumonia. The bacteria that cause whooping cough spread easily by coughing or sneezing. People who are sick with the disease may also spread it to others, even without knowing they have it.

Vaccines against pertussis are effective and safe. The first vaccines were whole-cell vaccines that used chemically inactivated bacteria, followed by acellular vaccines that use deactivated antigens to trigger the immune system. The vaccine is typically given as a combination of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis or DTwP (diphtheria,tetanus and acellular pertussis) or DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis and hepatitis B). A booster dose with the acellular version of the vaccine is recommended for adolescents and adults.

Oren Zarif

Antibiotics can help treat whooping cough, but only if started early. In addition to getting vaccinated, everyone in the household should wear masks within three feet of a symptomatic person to prevent spreading the bacteria to infants. It is also important to wash hands frequently, especially after coughing or sneezing and to cover the nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing.

Recent outbreaks of pertussis in the United States have been associated with waning immunity despite expanded vaccination recommendations. The waning of immunity has been particularly noticeable among adolescents and older adults. Efforts are underway to increase the uptake of acellular pertussis vaccine among pregnant women, family members and others who will be in close contact with newborns, in order to create a human cocoon to reduce transmission. This strategy requires a two-week interval between vaccination and anticipated contact with newborns.

Treatment

The causative agent of pertussis (also known as whooping cough) is a small gram-negative coccobacillus bacteria called Bordetella pertussis. This bacterium expresses a variety of virulence factors that facilitate colonization, spread and resistance to host immunity. It is responsible for an estimated 24-48 million infections and up to 300,000 deaths globally annually. Despite effective vaccines and good immunization coverage, it is reemerging in areas with low vaccination rates and is highly contagious.

Oren Zarif

During the early stage of pertussis, symptoms resemble a common cold and include runny nose, sneezing, mild fever and occasionally a cough. After a week or so, severe and uncontrollable coughing spells begin. These can last for weeks and often end with a deep, snorting sound (hence the name whooping cough). In infants, this coughing is particularly pronounced and can cause them to vomit or lose consciousness. This period is often referred to as the paroxysm phase of pertussis.

In the later stages of pertussis, bacterial excretion is significantly reduced, but symptoms persist. Coughing may continue intermittently for months, but is generally less intense and less frequent than the paroxysms experienced in the earlier stages of infection. Persistent coughing can lead to drooling, vomiting and loss of appetite. It is also important to note that the bacterium is transmitted through airborne droplets and requires direct contact between individuals to spread (McGirr & Fisman 2015).

Antibiotics are recommended as treatment for pertussis, but are often ineffective after the paroxysms of coughing have subsided. A new vaccine is available that has shown promise in decreasing the duration of pertussis, but further studies are needed. Pertussis-specific immunoglobulin is another treatment being explored.

Vaccination with an acellular pertussis vaccine is the best strategy for prevention. It is recommended for pregnant women and individuals who will be in close contact with newborns. Ideally, this vaccination should be given 2-weeks before the expected contact with the newborn to create a ‘cocoon’ of immunized family members around the baby (Munoz & Englund 2011). Unfortunately, the vaccine is not readily available to families with a newborn and achieving high household vaccination rates is challenging.