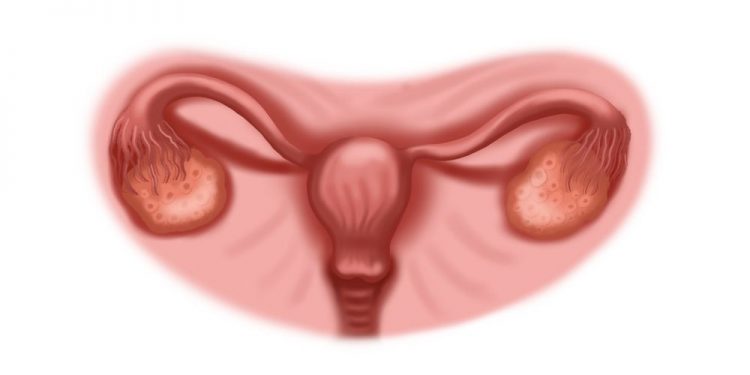

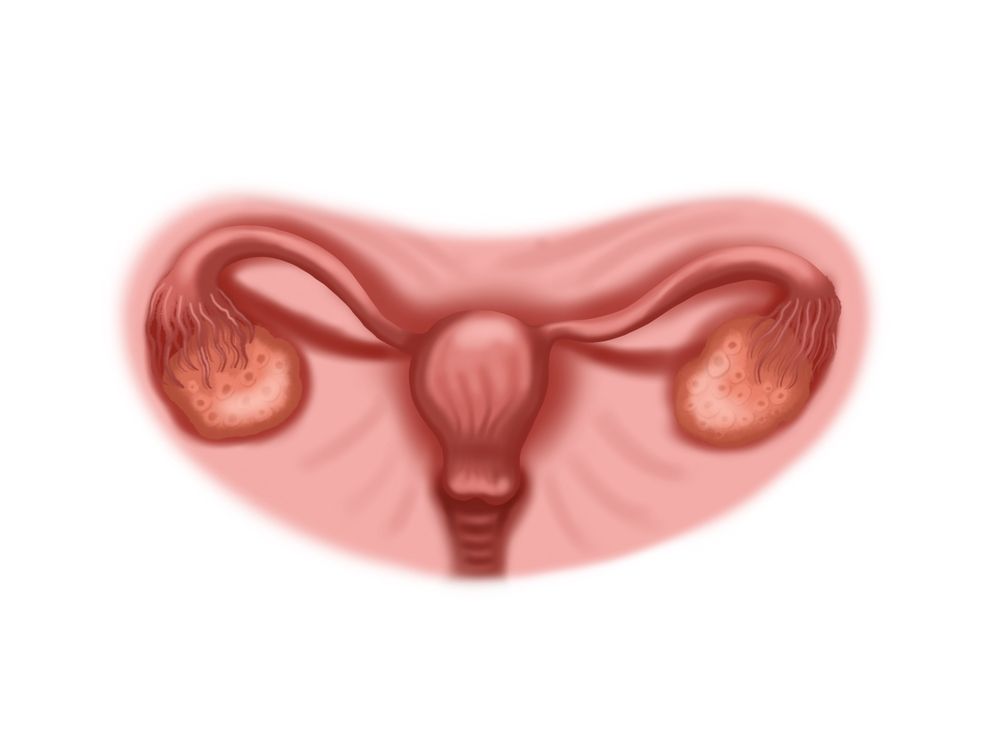

During a normal menstrual cycle, the uterus develops a lining each month. This lining serves as a cushion for the fetus. After ovulation, the endometrium thickens to prepare for implantation and then, during the next month, if there is no pregnancy, the uterus sheds the lining through menstruation. If the lining becomes too thick, it can start to grow in places outside the uterus. This is a condition called endometrial hyperplasia. It is not cancer, but it can increase the risk of developing cancer of the uterus (endometrial cancer).

Women who experience abnormal bleeding are at higher risk for endometrial hyperplasia, especially those who have been on hormone replacement therapy with estrogen only. This is because the estrogen in the estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy may trigger a buildup of the endometrial gland cells. It is not clear what causes the overgrowth of the gland cells, but it may be related to genetics or a woman’s age. In addition, women with a long history of irregular or absent menstruation or a family history of endometrial cancer are at increased risk.

When endometrial hyperplasia is found, your doctor can evaluate the severity of it by performing a tissue biopsy. They will use a device that inserts into your vagina to see the lining of your uterus. They can also perform a procedure called a dilation and curettage (D&C) which involves opening (dilating) your cervix with a thin instrument, then using a tool to remove the endometrial cells that are growing outside the uterus.

The results of the biopsy determine what kind of treatment you receive. If your uterus lining has mild or moderate hyperplasia without atypia, you can be treated with hormones and the likelihood of your endometrial cancer going away is very high. You will need to continue taking hormones, even after the hyperplasia goes away, for a few months to ensure that the regrown tissue does not begin to grow outside your uterus.

If you have atypical hyperplasia, the risk of developing cancer is higher and your doctor might recommend a hysterectomy, which is surgery to remove your uterus. This is only recommended for women who no longer want to have children.

The best way to prevent endometrial hyperplasia is to avoid estrogen-only hormones after menopause, and to take a combination of estrogen and progestin. This can be done with birth control pills, which contain both estrogen and progestin or with an intrauterine device (IUD). If you have a long history of irregular or absent menstruation, losing weight, and avoiding smoking can all help reduce your risk for this condition. If you have a hysterectomy, your risk for future cancers decreases, but you will still need to be monitored regularly. If your hyperplasia changes to atypical cells, you should contact your healthcare provider right away.