When cancer spreads to other areas of the body, it is called metastasis. When it spreads to the lungs, it is called metastatic lung cancer. Metastatic cancer is a late stage of the disease. It has already spread beyond the original site and is harder to treat than cancer that doesn’t spread.

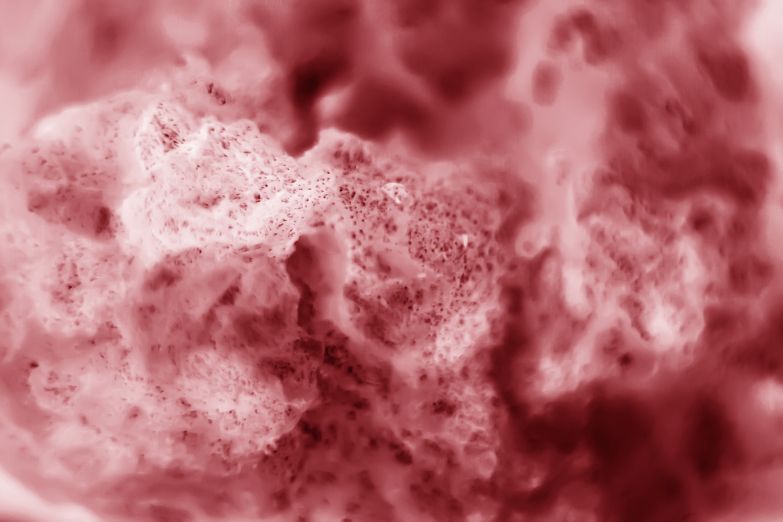

Cancer cells are normally able to divide and make more copies of themselves, but sometimes they develop mutations that cause them to continue dividing when they should not. The uncontrolled growth creates masses of tissue, or tumors, that keep the organs from working properly. Cancers that start in the lungs are called primary lung cancer. Cancers that start in other parts of the body and move to the lungs are called secondary cancers.

A person with metastatic cancer may not have any symptoms, or the signs and symptoms of the disease might be similar to those of other conditions. For example, a cough that does not go away might be caused by a viral infection or an allergy. But a persistent cough that is not relieved by other treatments might be caused by cancer spreading to the lungs. People who have a persistent cough might be referred to a doctor for a medical evaluation. The doctor might order blood tests, such as a platelet count, to help determine what is causing the cough.

If the doctor believes that the symptom is caused by metastatic cancer, they might ask the person to undergo bronchoscopy, a procedure that allows them to examine the interior of the airways in the lungs. This involves inserting a tube (bronchioscope) down the throat to see inside the trachea, main bronchi, and bronchioles. The doctor might also take a sample of cancerous tissue for testing.

The laboratory tests that doctors use to test for metastatic cancer include blood work, imaging, and a biopsy of the suspicious area. The results of these tests can help identify if the cancer is metastatic and what part of the body it came from. They might also help identify which treatment is most likely to be effective.

To find out if the cancer originated in the lungs or in another area of the body, doctors might look for specific types of cell mutations. They might then compare the mutated cells in the metastatic tissue to the mutated cells in the initial cancerous site. They might also look for patterns in the way the mutations are distributed, such as whether a cluster is unique to the original site or shared between sites.

Researchers have developed methods to study the DNA of both the primary and metastatic tumors. They have found that for some patients, the mutations in the metastatic tissue are different from those in the original tumor, suggesting that they were not seeded by the original tumor. In other cases, the timing of the divergence between clones was similar in the primary and metastatic samples. This suggests that the clone that seeded the metastatic cancer did not remain monoclonal, or that additional clonal sweeps occurred after the initial dissemination of the primary tumour.