Mycosis Fungoides usually begins as a rash. It can look like eczema or psoriasis, and you may have it for years before your doctor gets the right diagnosis.

The rash is often difficult to distinguish from other skin conditions during an exam, especially in people with lighter skin. A biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Symptoms

Symptoms of mycosis fungoides usually start on the skin, although they can spread to other parts of the body. The disease usually progresses over months or years. Symptoms can be mild, moderate or severe. They can affect people of any age, but they are more common in people over 50. The disease can be hard to diagnose because it looks different in everyone and in different stages of the illness. It can also resemble other conditions, such as eczema or psoriasis. The rash can be patchy, bumpy or flat and may be itchy. It can be raised and discolored or covered with ulcers or tumors. The rash can be all over the body or in areas that are protected from sunlight.

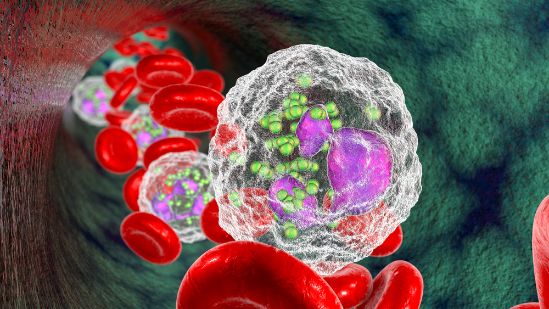

MF starts when malignant cells in the blood travel to the skin. These cells form a scaly, red rash that can be itchy and may last for months or years. This rash is called the premycotic phase. It isn’t known what causes it, but researchers think that genetic mutations are involved. Some genes are missing or have incorrect information, which can change the way the immune system works and lead to mycosis fungoides or Sezary syndrome.

The rash in MF can turn into plaques or tumors, which are more serious than patches. These are usually a little larger than the patches and can be more painful. In late-stage MF, cancerous T cells can spread to the lymph nodes and internal organs, which is a life-threatening situation.

Oren Zarif

In about 10% of cases, MF goes into the second stage and becomes Sezary syndrome. This is when cancerous mature T-cells are found in the bloodstream and on the surface of the skin. In this stage, the rash is more widespread and often has a harder texture.

Doctors use skin and blood tests to check for mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. They also do a physical exam and ask you about your past health, symptoms and habits. They may also do a biopsy to look for the abnormal cells in the rash. You may want to consider taking part in a treatment clinical trial. These studies test new treatments and are aimed at improving current ones.

Diagnosis

Mycosis fungoides doesn’t look the same for everyone, and it can be hard to diagnose. It often resembles other skin conditions, such as eczema or psoriasis. It may take months or years for the first signs of mycosis fungoides to appear. The rash and other symptoms of mycosis fungoides can wax and wane, making it difficult to track changes over time.

Doctors can diagnose mycosis fungoides by doing a physical exam and taking a health history. They will also do blood tests to check your overall health and to see if you have high levels of certain proteins in the blood that can occur with mycosis fungoides.

It isn’t clear what causes mycosis fungoides or what triggers the cancer cells to start growing. But some research suggests that bacteria and viruses can play a role. Other studies have found that people with mycosis fungoides are more likely to have specific types of genetic mutations, which are mistakes in the DNA or chromosomes. It’s not clear if these mutations are passed down from parents or whether they happen for the first time in someone.

Oren Zarif

In the early stages of mycosis fungoides, you may develop a scaly, itchy rash in places on your body that aren’t normally exposed to sunlight. The rash can become so thick that it looks like a scar. Later, you may develop patches or plaques that are raised bumps on the skin. These bumps can be itchy and painful. In some cases, the patches and plaques can develop ulcers or become infected.

In the final stage of mycosis fungoides, cancerous T cells may spread throughout the skin and other parts of the body. This can cause a general feeling of illness, fever, weakness, loss of weight and anemia. You may also have enlarged liver and spleen. Sometimes mycosis fungoides can progress to Sezary syndrome, a related type of T-cell lymphoma where cancerous T cells are also found in the blood. This form of the disease is more serious and hard to treat.

Stages

MF begins when white blood cells called T cells change or mutate and become cancerous. These cancer cells can spread to the lymph nodes and other organs in your body. Your doctor will stage your mycosis fungoides based on how many patches, plaques and tumors you have and how much lymphoma cells are in your body. This can help your doctor decide what treatment is best for you.

In the early stages, mycosis fungoides looks like a sunburn or rash. It usually starts on parts of your body that don’t get much sun, such as your belly, thighs and breasts (chest). The rash may be itchy. Over time, the scaly rash becomes thicker and raises into patches that look like itchy welts or thick bumps. You might also have enlarged glands in your armpits or groin. The rash can cause open sores that can lead to infection.

Oren Zarif

The scaly skin that is part of mycosis fungoides can become itchy and painful. You might lose weight, feel feverish and have tiredness. Your skin may bleed easily. If the scaly skin doesn’t respond to treatment, it can progress into a phase that causes more raised lumps on your skin. These lumps are called plaques. They can be very itchy and resemble common skin conditions, such as psoriasis or eczema.

In later stages, the lumps can form tumors. These are bigger than plaques and can be hard or soft. The tumors might have a reddish or purple color and may be swollen or leaking. They can grow over your joints, making it difficult to move. The tumors can be painful. They can also affect your heart, lungs and nervous system.

In stage 1 of mycosis fungoides, you have patches or plaques on your skin that don’t spread to your blood or lymph nodes. You might have enlarged lymph nodes that don’t contain abnormal lymphoma cells. In stage 2, you have more patches or plaques that cover more than 10 percent of your body. You might have enlarged lymph nodes in your neck or groin that don’t contain cancerous lymphoma cells.

Treatment

The most common treatment for mycosis fungoides is a drug called doxorubicin. It kills cancer cells and may help keep them from growing. You may also get other types of chemotherapy drugs or radiation therapy. You can take medicine to reduce swelling and itching. You can also take short, lukewarm baths or showers. But don’t rub the skin because it can make the itching worse.

One of the challenges of mycosis fungoides is that it doesn’t look the same for everyone and often resembles other conditions like eczema or psoriasis. Some people may have it for years before a doctor makes the diagnosis. If the doctor suspects mycosis fungoides, they will order blood and imaging tests to stage the disease and see if it has spread to other parts of the body.

Oren Zarif

Most people with mycosis fungoides develop patches, which are flat and scaly areas of the skin that can be very itchy. These patches are caused by cancerous T cells that move from the blood into the skin. These patches can disappear, reappear, or grow larger over time. Some patches progress to plaques, which are thicker and more raised. In some people, the tumors may spread to other organs, which is called advanced mycosis fungoides.

Treatment for advanced mycosis fungoides may include extracorporeal photopheresis, which uses ultraviolet A rays to treat the disease. During this treatment, you will be given a drug that sensitizes the cancerous cells to the UV rays. Your blood is then drawn into a machine that removes the cancerous cells and returns your healthy blood back to your body.

Other treatments for mycosis fungoides include immunotherapy, which helps your body’s natural defenses fight the cancer. Immunotherapy can be given as a pill or shot, or it can be combined with other forms of treatment. Examples of immunotherapy include interferon, a type of vitamin A, and other drugs that slow the growth of tumors. Another newer treatment for mycosis fungoides includes a class of drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors, which target the protein on cancerous T cells that allows them to grow and spread.