Myeloid refers to a group of blood cells—including neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes, and platelets. Cancers that affect these cells are called myeloid leukemias.

A myeloid leukemia begins in the bone marrow and then moves to other parts of the body, where it can spread (metastasize). The tumors grow quickly and may crowd out healthy white blood cells and platelets, leading to low numbers of these important blood cell types. Some myeloid leukemias cause no symptoms, while others can cause serious, life-threatening problems such as infections, bleeding disorders, and anemia.

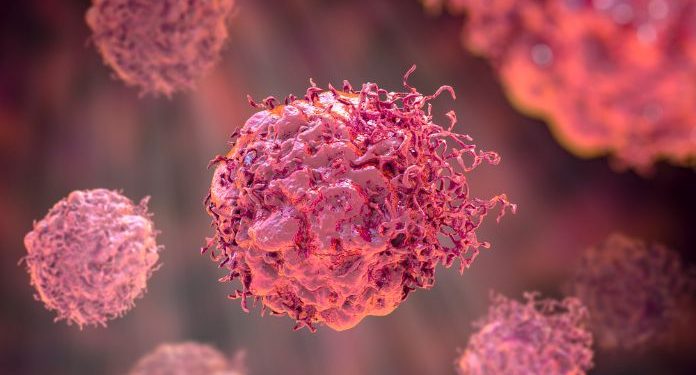

Cancerous myeloid cells can be identified in a blood sample by medical pathologists who examine the cancer cells under a microscope. They look for specific changes in the genes that control how your cells grow and function.

These changes are called mutations. They can be caused by inherited genetic mutations, or they can happen because of exposure to certain chemicals or treatments. Many of the treatment options for myeloid leukemias focus on drugs that kill the cancer cells or stop them from growing or spreading.

During embryonic development, myeloid progenitors give rise to microglia in the brain, Kupffer cells in the liver, and Langerhans cells in the skin. These cells also seed the lungs before birth, where they differentiate into long-lived alveolar macrophages.

The WHO 5th edition classification of haematolymphoid tumours has been developed to hierarchically catalogue myeloid neoplasms within a single relational database. The system retains the broad clinical and biologic categories from previous editions while incorporating new discoveries in the areas of cellular differentiation and germline predisposition, including gene fusions. The classification is organized into categories, families, and types with an emphasis on dominant clinical attributes as well as cellular characteristics including immunophenotyping and molecular data.

The main types of myeloid leukemia are acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), and myelodysplastic syndrome with myeloproliferative features (MDS/MPN). The underlying cause of these cancers can be different, so each type has its own treatment options.

Blood tests can tell your doctor if you have too few or too many white blood cells (neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes) in your body. Your doctor can also use imaging tests to get a more detailed picture of your bones and blood. These include CT scans, MRIs, and ultrasounds. You might also have a bone marrow test, which involves taking a small amount of blood and bone marrow from your hip or breastbone. The specialist then looks at the marrow under a microscope for signs of cancer.

You can lower your risk of developing myeloid leukemias by avoiding smoking and limiting contact with chemicals. You should also have regular checkups to find out if you have any health conditions. This includes getting immunizations. A doctor might also order a blood clotting test to see if you have too few or too many platelets in your body. This can help identify certain health conditions, such as lupus and hemochromatosis. The test can also detect if you have an infection.