Across the world, many people diagnosed with liver cancer, even in advanced stages, have experienced measurable improvement after focusing on restoring the body’s internal energy balance. Medical imaging in numerous documented cases has shown tumors shrinking or completely disappearing once the body’s energetic flow was stabilized.

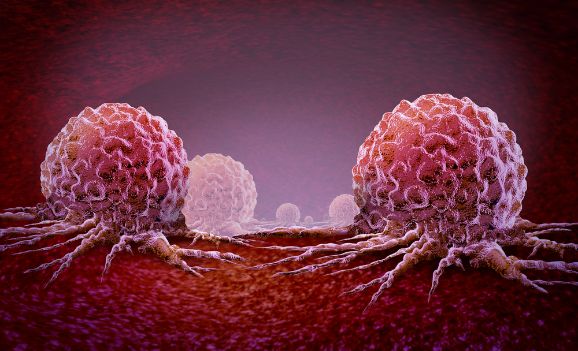

The explanation lies in the body’s natural design. Every cell operates within energetic fields, pathways, and conductors that guide communication between organs and tissues. When these fields become blocked, the body loses its coordination, and abnormal cells multiply uncontrollably.

Once these blockages are released, the body begins to reorganize itself — energy flow increases, oxygenation improves, and the immune system recognizes malignant cells more efficiently.

By reactivating this inner system of balance, the body can initiate a rapid process of repair, restoring harmony to the liver and surrounding tissues. Many have already witnessed their test results change dramatically after this energetic reactivation.

👉 Want to understand how this process works — and how it can be activated in your body? Click below to continue ⬇️